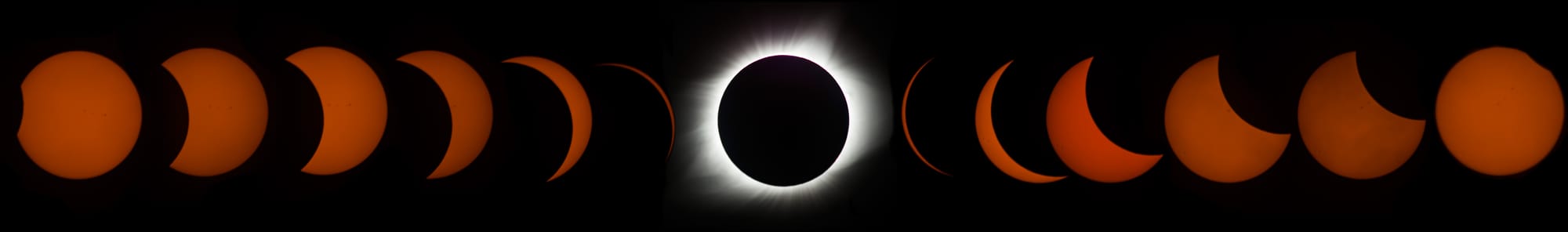

Total Eclipse

The memory of projecting light on the shirt cardboard stands out only because it was the same afternoon we were taken to see the play, Peter and the Wolf.

What was it like to be working in the yard, or noticing from in front of the kitchen sink that it was getting dark early outside because a solar eclipse was sneaking up on you where you lived? We have had the know-how to anticipate eclipses for almost three hundred years, but for a good portion of that time word traveled slowly. As with the weather, which people have been trying to predict accurately since before the Babylonians, there have been experts around who could read the signs, but for the rest of us, it was the Old Farmer’s Almanac, red skies in the morning or red skies at night, and Grandfather’s aching knee.

I could swear there was an eclipse over our house in Connecticut when I was a boy because I remember building a pinhole projector using a couple of shirt cardboard. There is no record of an eclipse at that time, so I must have been running some other experiment. Maybe just observing the sun, although why would that have been interesting, looking at a small circle of light on a gray surface? There were plenty of more interesting things to do with sunlight relying on a magnifying glass to burn holes in leaves and things. I confess that various small bug-like creatures were sacrificed that way in the interest of science. It is hard to look back on.

The memory of projecting light on the shirt cardboard stands out only because it was the same afternoon we were taken to see the play, Peter and the Wolf. Funny how these associations persist, perhaps inaccurately, but it is how they are filed in my head. “Bring all that cardboard inside—don’t leave it on the lawn—get ready, we’re leaving for Peter and the Wolf.” It was an afternoon performance. The highlight was the actor who played the wolf. He came out on stage ahead of the show, sat at a table, and while talking to us, describing the upcoming action, made up his face, slipped into a furry sweater, pulled on furry pants, and disappeared under a wolf’s head. When he appeared later, menacing and devouring, no one jumped out of their seats or started crying.

The next total eclipse of the sun visible in the U.S. will be in August of 2044, but it will be remote to us, arriving from Greenland via Canada, running out of gas mid-afternoon after traveling over only three northwestern states. If I happen to be here, I will have to watch it on television, or whatever we are watching things on by then. A virtual reality headset, maybe, providing a thoroughly immersive eclipse experience, as if I was there. Can’t get to the eclipse because you are eighty-seven years old? We’ll bring it to you.

It is not the same as standing in your garden as the sun is slowly blotted out overhead. Search as I did online, I could find no reference to when a total eclipse would be that personal for us again in New England, only that the last such event was a century ago. Fair assumption it will be another century, making it a once-in-two-lifetimes occasion.

For that reason, I was resolving not to miss it by choosing to be away or napping on the couch in the basement, as has happened with other phenomena such as asteroid displays that invariably occur after midnight. But, then, the call came to help with the grandchildren for two days in Boston, presenting me with a simple choice between natural wonders. It won’t be a total loss, eclipse-wise, but it will shave off a few percentage points of totality—the technical term, you know when speaking about eclipses.

I am more attached to the totality of my experience with the grandchildren, knowing each day that goes by with them will never come around again. Plus, if I am still here in 2044, I will need their help with the virtual reality headset.